In The Good Way: Looking at Tribal Humor

- Tiffany Midge

- Jul 19, 2023

- 9 min read

Updated: Jan 21, 2024

By Tiffany Midge

1. The Indigenous Whoopee Cushion School of Comedy

Since time immemorial my Indigenous ancestors have practiced the sacred art of comedy. Comedy gold classics such as the whoopee cushion predates first contact. And chokecherry-cream-pies-in-the-face are actually paleolithic. Cave wall paintings provide the earliest clues for the existence of ancient Native American shtick. Whoopee cushions, sometimes called “toot pillows,” were originally made from the bladders of deer or bison; the bladder was inflated and tied off, much like a modern-day balloon. Prehistoric examples of whoopee cushions along with shards of ancient pie pans were discovered at an archeological dig near the famous Corn Palace in Mitchell, South Dakota. Evidence of coup sticks were also excavated, proving that slapstick (quite literally a “slap stick”), was a highly regarded cultural custom.

Except for the opening line “Since time immemorial my Indigenous ancestors have practiced the sacred art of comedy,” I’m obviously joking. Suffice to say that in whatever direction my ancestors’ humor may have taken, there have been very well-established conclusions about Native humor over the decades; a starting point beginning with author, activist, and historian, Vine Deloria Jr. (Standing Rock Sioux). His seminal essay “Indian Humor,” from his book “Custer Died for Your Sins,” details specific jokes—from the “Indian jokes canon” as it were, which is cited repeatedly in Native Studies scholarship. Deloria wrote: “One of the best ways to understand a people is to know what makes them laugh. Laughter encompasses the limits of the soul. In humor life is redefined and accepted. Irony and satire provide much keener insights into a group’s collective psyche and values than do years of research.”

Left: Original Book Cover, Custer Died for Your Sins, An Indian Manifesto, written in 1969 by Vine Deloria, Jr.. Right: New Print Edition 2014. "The book is considered one of the most prominent works ever written on American Indian affairs. Custer asserted a vibrant Indian presence, drove the tribal struggle into the national spotlight, and became a centerpiece of the movement for tribal “self-determination,” a principle now recognized in tribal, federal, and international law,"

After so many years one might wonder if his essay holds up; is his essay still relevant in 2023? Definitely so, particularly the Custer jokes he cites. Natives still enjoy a good Custer zinger evidenced by how many memes and cartoons I see on my social media feeds, especially around June 25th, known as Battle of the Greasy Grass or Battle of Little Bighorn.

In fact, because of social media, Native satire is more accessible than ever. TikTok, Instagram and Facebook are the new smoke signals, the new moccasin telegraph. Some of the humor would make church ladies clutch their pearls—or rather, cause those strait-laced aunties to clutch their beads (an exception being Willie Jack’s Auntie B, portrayed on Reservation Dogs, whose beadwork is rather, um, interesting). I imagine Deloria would LOL. Heartily.

Photo of Auntie B's(character in Reservation Dogs) beadwork. Photo by Tiffany Midge.

If one wonders why Indians might appreciate saucy humor, they need only to look at creation stories and “folklore” of tribal peoples: our stories are full of sexual mishaps, risqué characters and ribald humor. There are stories about tricksters lusting after various targets, of young women seducing star people, vagina dentata tales and more.

2. Indian Humor Takes Its Gloves Off

In the aftermath of the Greasy Grass battlefield, was it humor, poetic justice or both, that prompted Cheyenne women to take up sewing needles and pierce the eardrums of the defeated Gen. Custer? The testimony being so that he might hear better in the afterlife—certainly better than when he was alive. And was a similar concept or sensibility used following the Sioux Uprising? The Dakota had been denied food or credit by the white traders while also prohibited to hunt outside of reservation boundaries. The people were starving and a trader, Andrew Myrick, said they should eat grass. Myrick was slain during the uprising and when his body was found, his mouth had been stuffed with grass. The Apsáalooke (Crow) artist Wendy Red Star refers to a story about Medicine Crow to describe “Indian humor.” Or more specifically, Apsáalooke humor. Red Star recounts that Medicine Crow possessed a “weird and wicked sense of humor.” When Medicine Crow and others killed some horse thieves, he cut off one of their hands, and later used the horse thief’s severed hand to shake hands with the reservation’s Indian agent. Red Star said, “the fact that this one guy had this bizarre sense of humor—I want people to know that.”

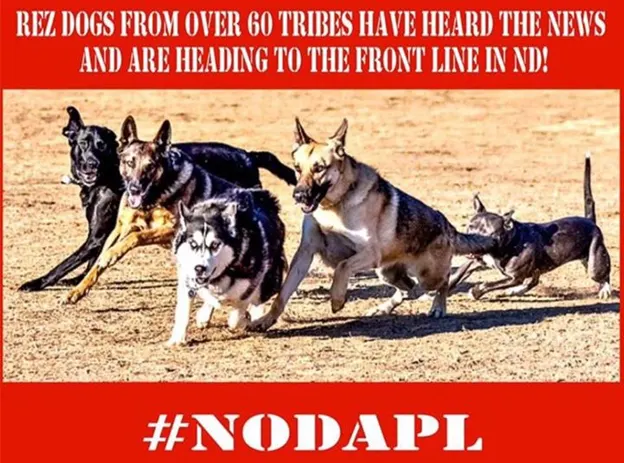

So, when I run across content that’s rugged or “cringe,” while at the same time really funny, I remember that Indians have been practitioners of this brand of humor, morbid or gallows humor –but in the good way—for a very long time, since time immemorial. One example of this scathing humor occurred during Standing Rock: Native folks were posting memes and jokes on social media that responded to the water protectors on the front lines being viciously attacked by dogs; memes and jokes which were posted less than 24-hours after protectors had actually been viciously attacked by dogs. Is this schadenfreude? Deriving amusement or pleasure from witnessing other’s misfortunes, or does it fall into the category of transcending trauma through humor and teasing—another hallmark of Native humor.

Memes of Rez Dogs heading to Standing Rock.

A more subtle and uplifting perspective of Native humor used during Standing Rock was Cannupa Hanska Luger’s Mirror Shield Project: dozens of protectors held up mirrors that reflected back upon riot police at the front lines. Parody holds up a mirror against adversaries through non-violent resistance. And in this instance, literally. While this frontline action would not necessarily be described as “humor,” much like piercing Custer’s eardrums following Greasy Grass or the irony of stuffing grass in Myrick’s mouth, they are consistent with a particular sensibility, which strikes me as a sort of distant cousin to humor. At least in hindsight.

Mirror Project, Project by Cannupa Hanska Luger, 2016, Standing Rock, ND. "Thanksgiving Day on the front-lines with riot cops reflected in the shield wall," Rob Wilson. Photo courtesy of Rob Wilson Photography.

3. Satire as Decolonial Coup Stick or Settler Spanking

All too often the media and publishing industrial complex seems very invested in our tragedy and redemption narratives—a kind of poverty tourism for public consumption. Of course, it’s fair to say that western literature has always been about death and tragedy, Native American literature easily finds its place within those themes: books, photojournalism, films about intergenerational trauma, about the plight of the Native Americans, our struggles, oppression, disappearances, and genocide. I often wonder about the opposite end of this continuum: intergenerational joy, creativity and humor. But let’s not leave out Intergenerational sarcasm, intergenerational whimsy or intergenerational weirdness! Can I even claim being Native if I don’t have a personal trauma narrative replete with a strong message of hope and redemption?

This concept of “Indian humor” or “Indigenous joy” represented in art, especially as a binary or even antidote to “Indigenous trauma” or “poverty tourism” for consumption or exploitation, rings hollow and prescriptive to me. It is helpful to consider humor and joy as being fundamental values encompassing the human experience while also considering there are definitive features, content and attitudes characterizing so-called “Native humor.” “Native Humor” is a very comprehensive discourse and I wonder about de-labeling it, perhaps inviting the idea that Indians are human (a bold thing to state, I know!) Can we conceive humor as human? Does “Native humor” require its label because we are not considered fully human?

Never mind—smashes huckleberry cream pie in face.

4. My Two Cents

When I wrote an article on Wendy Red Star’s work for The New Yorker, during the editing phase I was asked to elaborate on the concept of “Indi’n humor,” particularly because Red Star’s work is quite often satiric. I was thrilled to throw in my two cents, especially for such a prominent publication. Rarely are Natives asked to contribute to such conversations, let alone discuss something as niche (at least to the mainstream) as Native humor. (Although, that’s certainly changing.) I submitted my “two cents”:

While “Indi’n humor” may contrast from American humor in a lot of ways, perhaps its most prevalent characteristic is how often it solicits explanation. And how self-referential it is, to the point that whenever a Native makes a joke, those who are listening respond by appreciatively acknowledging their use of “Indian humor.” After centuries of being mischaracterized as stoic and austere, it is plausible, even necessary to self-reference our use of humor as a means to reassert our humanity. And of course, this in itself is an example of Indi’n humor. Without shared context or insider knowledge of history, or lived experience, certain ironies and particularly gallows-brand humor—another tell-tale signature—can’t be fully appreciated beyond the surface.

Not surprising, the paragraph was cut. Too tangential and off topic I would guess. I’m not sure “Indi’n humor” can be described in less than fifty words, can it? The editors might’ve thought I was being cheeky in my response—"how often it solicits explanation. And how self-referential it is…” Except that this is very true! I hear so often that Native humor was our means of survival; that Native humor is an example of our resiliency; that Native humor is medicine, laughter is healing, which are all accurate features of our cultures, but what I had been trying to describe was when a joke is made, in whatever setting, all too often it’s bookended with these truisms. And while these are certainly uplifting, at times I’m impatient with their predictability. I think our humor is more complex than that. A lot more complex than I have room to explore in just this one essay, considering there’s more than enough about Indian humor to fill an entire book.

5. Indians Appearing in TV Situational Comedies and RomComs…Wait, What?!

With the emergence of Indigenous comedians and showrunners finally given a platform within Hollywood entertainment and television sitcoms, hilarious shows like Reservation Dogs and Rutherford Falls are finally offering a perspective not often viewed on the national stage. Indigenous humor, or “Indi’n humor,” is nothing new, of course—just its reach has expanded. It’s gone from “grass (dance) roots” so to speak, to mainstream. And while this development certainly has its benefits: optimizing awareness and visibility of Indigenous issues obviously, but also it sends a strong message that we still exist. We’ve always been here, wise-cracking and laughing with our grandmas and grandpas, aunties and cousins around the kitchen table, meeting up at powwows, graduation picnics, and well, yes, funerals. We’ve always found that circle to join in where we joke, tease, stretch the truth, and entertain. And I’m left to wonder why it has taken America so long to figure out that Indi’n humor is worth the production value, worth the trouble of investing capital into? To create “content” for television? And not just television series but also theater productions, stand up comedy and films.

Top Image: Reservations Dogs Promotional Image on FX, streaming on hulu. The comedy/dramedy series tells the coming of age story of a group of friends growing up on a reservation in Oklahoma. The photo features main character Bear Smallhill's(D’Pharaoh Woon-A-Tai) spirit guide William Spirit Knifeman(Dallas Goldtooth). The series director, writers, and cast are all Indigenous.

Bottom Image: Photo promo for Rutherford Falls, a streaming series on Peacock. The comedy/dramedy tells the story of relationships being tested as their own relationship to their town's colonial white-washed history is confronted through meta twists and ironic flips of the script. The show co-created by Native screenwriter Sierra Teller Ornelas,is mainly staffed by Native writers. Some episodes are directed by Native directors, and the cast features Native actors portraying Native characters and their stories.

It’s especially gratifying to see the shift going from non-Natives writing about Indigenous people, to Indigenous-created stories and sit-coms written by Indigenous people. The shift is dramatic—the white, colonialist gaze being supplanted by an obviously more accurate and dynamic perspective is worthy of celebration. And in that development, Indigenous creators are being directly compensated, also. There’s no denying that Indians participate in capitalism as much as the rest of the world. So, receiving story credit and financial gains from telling our own stories represents significant progress. It benefits our young people to see themselves represented in media. Not as wooden stereotypes, butts of jokes or mockeries, but as fully developed and complex human beings.

6. Let Me Just Leave You with This

Since time immemorial my Indigenous ancestors have practiced the sacred art of comedy. It is not widely known that legendary Hunkpapa leader Sitting Bull, Tȟatȟáŋka Íyotake, was a notorious practical joker. He often pranked Red Cloud during tribal council by placing a whoopee cushion

beneath Red Cloud's buffalo robe with hilarious results! But he stole all of his best material from the band's heyoka, Pretty Wallowing Woman, and passed it off as his own. In fact, it was Ernest Iron Necklace, a great, great grandson of Pretty Wallowing Woman who originated the Take-My-Wife-

Please shtick that was made famous by comedian Henny Youngman. In a 1967 Newsweek article, the famous “King of the One-Liners” credits Iron Necklace as being his inspiration for comedy: "Iron Necklace was my comedy spirit 'patronus,'" Youngman said.

Tiffany Midge (Standing Rock Sioux Nation) was raised by wolves in the Pacific Northwest. Her book of essays “Bury My Heart at Chuck E. Cheese’s” was a finalist for a Washington State Book Award and her work has appeared in The New Yorker, The Brooklyn Rail, First American Art Magazine, World Literature Today, McSweeney’s, and more. Formerly a humor columnist for Indian Country Today, she’s currently a columnist for High Country News. Her honors include The Wilder Prize; Submittable2020 Eliza So Fellowship; a 2019 Pushcart Prize; the Kenyon Review Earthworks Indigenous Poetry Prize; a Western Heritage Award; and a 2019 Simons Public Humanities fellowship. Midge aspires to be the Distinguished Writer in Residence for

Seattle’s Space Needle and considers her contribution to humanity to be her sparkly personality.

Learn more about the author at: https://tiffanymidge.wixsite.com/website

Find "Bury My Heart at Chuck E. Cheese's" HERE

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE...

Comments